Ancient Psychedelics and the Future of Healing: A Need for Protection & Preservation of Rock Art

A kayak trip to study Lower Pecos River Rock Art, Peyote and Deer in the Vanishing Murals of West Texas, and the need for Cultural Humility in Psychedelics Research

Hidden in the remote canyons of West Texas, 4,000-year-old rock murals may represent the oldest visual record of psychedelic healing in North America. Radiocarbon-dated to the Middle Archaic period (2,250–800 B.C.E.), these pictographs line the limestone walls along the Lower Pecos River. They depict antlered shamans mid-transformation, serpentine catfish goddesses tied to lunar myths, and panthers pointing the way to freshwater springs—symbols that reflect a deep entanglement of ecology, medicine, and spirit.

Archaeological evidence confirms the use of peyote in this region during the same time period. The rituals and symbols preserved in these murals mirror modern-day Wixárika (Huichol) ceremonies, where peyote is hunted like a deer and consumed in healing rituals grounded in cosmology and landscape.

In 2021, I traveled by kayak with my art professor Mark Monroe and close friends (Veronique Tessier and Sierra Ford) to reach many of these mural sites, often navigating steep muddy banks and hillsides or negotiating entry onto private cattle and sheep ranches from rocky edges of the Pecos canyon.

As a medical student today conducting psychedelics research at MD Anderson Cancer Center—specifically studying how psilocybin might help cancer patients cope with pain and existential distress—I’ve come to see profound overlap between this ancient knowledge and modern science. Patients in our studies often describe a powerful sense of connectedness, a breaking down of boundaries between self and world. This echoes what neuroscientist Robin Carhart-Harris calls a “more dynamically flexible and integrated” brain state induced by psychedelics.

This story sits at the crossroads of three themes:

Ancient Healing Meets Modern Neuroscience

The Lower Pecos shamans were not just artists or spiritual guides—they were healers, using peyote to bridge inner and outer worlds. Today, psychedelics are being used in psychiatric settings to treat addiction, depression, PTSD, and end-of-life anxiety. The murals provide a visual and cultural lineage of this therapeutic tradition, grounded not only in the brain, but in land, story, and ceremony.

Healing

In Indigenous worldviews from West Texas to Northern Mexico, health is relational: between people, ancestors, plants, animals, and place. In a sense, this resonates with the One Health framework, which connects human well-being with the health of ecosystems. As psychedelics re-enter Western medicine, these traditional frameworks must be honored—not erased. Houston-based bioethicist Amy McGuire warns that Western medicine’s focus on individualism must evolve to recognize the interdependent, communal nature of true healing.

A Race Against Time

The murals are rapidly vanishing—damaged by flooding, heat, neglect, and vandalism. The Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center, supported by the National Science Foundation, is leading an urgent campaign to digitally preserve the murals before they disappear entirely. Their work is a form of medicine too—healing the historical rupture by archiving the stories etched into canyon walls. Yet even this vital preservation effort is under threat, as government funding for ecological and cultural research grows precarious.

This project is not just about psychedelics, or ancient art, or modern medicine. It’s about reweaving a relationship with healing that sees no separation between mind, body, culture, and earth. As Wixárika elder and shaman José Luis Ramírez “Urraumire” once said in reference to traditional peyote pilgrimages:

“We do not want to let them contaminate the sacred places; we want to leave something beautiful for our families... Let us raise and sow that sacred seed, and let our planet not end, so that all that is beautiful remains.”

In a moment where psychedelic medicine is accelerating toward mainstream acceptance—even in Texas—these ancient murals serve as a caution and a compass. They remind us that true healing is not just a chemical or a clinical outcome. It is a sacred, storied practice—one that requires reverence, responsibility, and the wisdom to listen.

Introduction:

Pecos River Style (PRS) rock art, one of the various types of pictographs found on the cliff overhangs and cave walls in southwest Texas, contains striking imagery and clues to the nature of ancient life in the area. The symbols and themes in the 4,000 + year-old rock paintings, stretching over concave limestone walls in colors of black, red, yellow, and white, might even relate to the continued cultural practices and beliefs of the Huichol people, who live today in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico. Images that might have represented primordial versions of their myths and rituals have been recorded on these rock canvases eons ago by the people that inhabited these desertous dwellings. Today, elders of the latest known Indigenous communities to live in the area, collectively known as the Coahuiltecans, recognize similarities to their creation myth in a particular site called the White Shaman Mural. Archeological findings in the area, biological and environmental circumstances, radiocarbon dating, and rigorous study of these paintings can help piece together an idea of the subject matter in the art itself. Artist and archeologist Caroline E. Boyd, PhD, one of the leading scholars in this area of study, has pieced together ethnographic accounts of myths and stories told by Huichol elders over the years for the purpose of illuminating cultural (pre-)context across time and space that might hint at the significance of these paintings, and what makes them sacred.

After visiting some of these sites myself at Seminole Canyon State Park, going on guided tours to Fate Bell Shelter, the White Shaman Mural, and viewing some hard-to-reach sites from the Pecos river via kayak, I have reflected on the challenges that this artwork faces for interpretation and preservation. In the present paper, I will present an evidence-based timeline for this artwork and provide archeological and scientific findings and relevant ethnographic accounts related to the theme of peyotism and deer-hunting present in the PRS pictographs, to support one of Boyd’s hypotheses. While there is significant historical and cultural evidence to define these art sites as sacred to the Huichol (And other Native peoples), they are also deserving of preservation and protection for their aesthetic qualities, as they are magnificent feats of human creativity that demand the eye of the viewer and inspire the imagination. The geometric and dynamic composition of these paintings, combined with the clever use of natural geological features, makes them uniquely interactive and compelling as works of art. Beyond their beauty, they also contain messages, relay cultural truths, and reveal intimate parts of ancient human life.

Background/History:

Understanding the rock art of the Lower Pecos requires historical context. Multiple overlapping art styles reflect a long continuum of human presence in the region. Three major styles are commonly recognized: Red Linear (perhaps the oldest, with small, simplified figures) (Boyd et al.), Red Monochrome (a later style showing more realistic animals and humans with tools like bows and arrows) (Boyd; Dering, Lower Pecos–Rock Art), and Pecos River Style (PRS)—the most complex and the focus of this paper—distinguished by its multicolored palette: red, black, yellow ochre, orange, and white.

These styles often appear within the same cave or canyon, emphasizing the need for careful dating. Archeological and radiocarbon evidence help contextualize them. Human activity in the region dates as far back as 10,000–12,000 B.C.E., with the earliest evidence found at Bonfire Shelter, including Bison antiquus bones and “Plainsview” dart points—the site of the first known bison run (Shafer et al.; Dering, Lower Pecos–Archeology).

By 6,550–4,050 B.C.E. (Early Archaic), tools like grooved rabbit sticks, coiled basketry, and cactus-fiber sandals appear at sites like Frightful Cave (Shafer et al.; Maslowski; Dering). Painted pebbles—charcoal or mineral-painted stones with faces and geometric shapes—also emerge, especially at Eagle Cave (Castañeda et al.; Boyd).

The Middle Archaic period (4,050–1,050 B.C.E.) saw earth oven cooking at Hinds and Baker Caves and widespread use of native desert plants like sotol and lechuguilla (Shafer et al.; Boyd; Dering). Drought and signs of dietary stress suggest population increases and environmental strain. PRS murals—some dating from 2,250–800 B.C.E. (Rowe)—appear in this period. Painted pebbles vanish briefly before reappearing with stylistic changes, and interestingly, PRS murals used mineral-based black paint, unlike the charcoal pigment on earlier pebbles (Castañeda et al.).

The Late Archaic (1,050 B.C.E.–450 C.E.) was marked by environmental cooling, bringing bison south and influencing migration. Central Texas dart styles arrived, and bison bones became more common in archeological layers (Shafer et al.). The Shumla dart point appears later in this period, possibly linked to new arrivals from northern Mexico (Boyd; Shafer). Red Linear rock art was once thought to originate here, though this dating is debated (Boyd et al., 2013).

PRS pictographs, spanning from the Middle to Late Archaic, showcase complex compositions: 12-foot panthers, sine waves, abstract forms, anthropomorphs, animals, and hunting tools—created using mineral pigments mixed with fat and applied with sotol brushes or molded as pigment “crayons” (Shafer et al. 138). Found in shelters like Fate Bell, these murals remain vivid today and may offer the clearest visual insight into the beliefs, tools, and cosmology of ancient Lower Pecos peoples (Shafer et al.; Boyd).

Left: Panther Cave PRS pictographs copied in watercolor by Forrest Kirkland in July, 1937 (Kirkland and Newcomb)

Right: Photo by Veronique Tessier of Panther Cave from across the river, January 2021

PRS pictographs are not alone, however. Red Linear & Red Monochrome paintings are found nearby or on the same rock walls at many of these sites in the Lower Pecos area. After Forest Kirkland precisely documented 43 pictograph sites in watercolor in Val Verde County in the 1930’s, W. W. Newcomb defined 35 of them as PRS paintings (Kirkland and Newcomb). They arranged these in time from what they thought to be oldest to most recent: PRS, Red Linear, Red Monochrome, and Historic. These divisions in art style are so obvious that most researchers initially assumed that each art style could be assigned to different ethnic groups or people groups that came through the area. Bison hunters were thought to have left the Red Linear style paintings when they chased bison herds further south in the Late Archaic Period. However, Boyd et al. published research in 2013 which completely disrupted the previous understanding. In “A Reassessment of Red Linear Pictographs in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of Texas,” the authors present a new chronology: Boyd and colleagues had found PRS painted characters, which Rowe (2009) had previously dated to be as old as 2,250 B.C.E.--800 B.C.E., painted over Red Linear paintings. This prompted the reexamination of some 444 figures across 12 sites of paintings, in which they found 38 cases of similar overpainting of PRS over Red Linear using microscopic analyses. Red Linear, paintings characterized by a typically small size (under 10cm in height), male and female anthropomorphs with curvilinear bodies and sex organs, and a range of similarly sized zoomorphs, are now understood as being painted before PRS paintings, at least in these particular sites.

Thus, in many important PRS pictograph sites, there might be overlapping symbols-- Red Linear and PRS, that could be confusing the modern academic interpretation of these artworks. Perhaps more importantly, the content of the artwork has been simplified to a great extent by those who reduce Red Linear paintings as only depicting the profane/mundane, and not ritualistic or sacred depictions. Though sexual acts seem to be depicted (Groupings of human figures positioned together with depictions of enlarged sexual organs), there are also examples of male characters wielding possibly religious paraphernalia, antlered anthropomorphs, and distorted/elongated anthropomorphs, all previously thought to be exclusively PRS themes (Boyd et al.). It might follow that whoever left the PRS paintings were somehow aware of the significance of the previously painted Red Linear paintings, even if this significance was only relevant to the choice of location. These various factors support the idea that multiple modern-day people groups have their historical and ancestral roots in this area, an idea we will return to in later sections.

Now that we have pieced together a timeline, this provides better context for analyzing the possible themes in the ancient PRS (PRS) artwork of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Caroline E. Boyd, who has been recording, studying, and reproducing this art by hand since 1989, has established the dominant line of reasoning for interpreting this art. To build her argument, she intertwined multiple levels of evidence from ethnographic literature, archeological artifacts, and relevant biological research, which she describes in the opening pages of her 2003 book, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos: “Cable-like arguments are developed by intertwining distinct, separate strands of evidence… These strands can be either mutually reinforcing or mutually constraining.” (27). While every step forward opens other doors to new questions, Boyd has certainly connected some compelling ideas about what some of the motifs (Which she defines as recurring themes supported by multiple pictographic elements) in PRS rock art might signify, and she has ethnographic and scientific data to back her up. Her argument that peyotism and deer-hunting were culturally connected for these ancient people and depicted in PRS pictographs is worth analyzing. In support of the significance of this motif, I will also present an evidence-based case for the significance of deer and peyote to the ancient inhabitants of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands (Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos).

Methods in Analyzing PRS Rock Art: Caroline E. Boyd

Boyd describes her extensive and methodical research procedure in her 2003 book. First, she records general information about the site, then takes photographs using a reference system similar to the Rock Art Photo Reference Form from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, numbering each photograph. Descriptive forms for recording rock art are filled out for each pictographic element at a site, five for each main type of element she has encountered: Zoomorphs (Animals), Centrastyled or “Skeletonized” Anthropomorphs (Polychromatic human-like figures with a form of design in the middle of their body, or decorations outside their body, thought to denote spiritual or descriptive significance) , Concentrastyled Anthropomorphs (Anthropomorphic figures without decoration, usually monochromatic), Therianthropes (Elaborate anthropomorphs with animal characteristics or features), Handprints and Geometrics. Next, field sketches are made to document faded areas and pictographic elements that are not as clear in photographs. Boyd and colleagues’ laboratory procedures are complex, because a rock art site must be artificially recreated. Extensive measurements and methodical categorization of photographic data collected in the field can lead to successful recreations for analysis. Slides of photos are projected, and then copied on large pieces of paper with the appropriate color of pencils and pastels. Once these renderings are completed, the data is analyzed. Boyd has applied this method to several sites, including White Shaman (41VV124) and Panther Cave (41VV83), which I had the opportunity to see when I visited the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. It is from these detailed renditions that she was able to spend time with the visual components and build the main arguments of her research (Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos).

Interpretation of Peyote & Deer Symbols in PRS Pictographs

A significant part of Boyd’s work consists of ethnographic histories and cultural themes she pieces together from Indigenous and Native peoples in the American Southwest and Mesoamerica, whose myths, beliefs, and symbols are most likely influenced by the traditional belief systems of ancient people groups in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, some of whom might have painted the PRS murals and panels long ago. (Boyd and Cox). In her 2016 book “The White Shaman Mural,” Boyd references Lopez Austin, a Mexican historian who writes of Aztec and Mesoamerican histories, who wrote in 1997 that the core stories of ancient tradition persist into the modern day traditions of Native culture, though the characters and details change. Specifically, Huichol historical and ethnographic accounts of myths were examined by Boyd, as well ethnographies from the Hopi and further south, the Maya. Boyd has now put forth several hypotheses over the years that now possibly connect PRS pictographs, specifically the White Shaman Mural, to cultural symbols and themes of the Huichol. First, she made several arguments about visual representations of the myths and ritual ceremonies of the Huichol; and more recently, she connected broad creation narratives from Mesoamerica and the American Southwest to visual components of the White Shaman Mural, focusing on the Huichol cosmology and cultural symbols. Her initial interpretations of shamanism and ritual being depicted in PRS artwork is widely supported, with similar interpretations given by many leading experts in the field over past decades. This stems from the archeological record that matches the symbols in the art. Depictions of datura seeds (from the jimsonweed, containing toxic and psychoactive chemicals), woven pouches and religious paraphernalia, and possible bloodletting instruments match these physical items found in the same area, and carbon dating places both to around the same time period-- the Middle Archaic (Shafer et al.; Boyd and Dering; Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos; Kirkland and Newcomb, Turpin). Similar items, particularly the datura seeds, have been connected to shamanistic rituals in several Native American cultures, as they help induce trance (Boyd, “Shamanic Journeys into the Otherworld of the Archaic Chichimec”;Boyd and Dering). In more recent years, however, Boyd has made additional arguments for the presence of peyotism and deer worship/hunting motifs in PRS pictographs, as well as other themes related to recorded mythologies of the Huichol. While this argument is connected to shamanism, it relies on ethnographic accounts for evidence. However, radiocarbon dating of ancient peyote buttons and environmental cycles help support her argument (Terry et al., “Lower Pecos and Coahuila Peyote: New Radiocarbon Dates”; Boyd and Cox).

An important concept when considering the setting of the PRS rock art is the longevity of nearby natural shelters, and how these would attract nearby people for generations upon generations, allowing for communication of ideas through the neighboring sites containing rock art. Occupational sites, natural shelters in which people cooked, weaved, and spent time living in, were revisited and used by many generations and different people groups, as evidenced by many layers of cultural debris in many caves and shelters (Maslowski; Dering, “Lower Pecos-Archeology”). In many sites, prickly pear pads were used for flooring along with woven matting, and these are found in multiple layers, suggesting that new living areas were simply built on top of what was previously there. In Arenosa Shelter, thousands of years of human habitation at different time intervals can be visualized by ashy “midden deposits” (Layers of ash from fires, other organic material left by humans) left in the earth, now exposed by archeological excavation (Dering, “Lower Pecos-Archeology”). Moorehead Cave, an example of a large occupation site that I visited, was extensively excavated in 1933 by Ed McCarson, and the Smithsonian has stored away many of the artifacts found here. Among them, Middle Archaic dart points like the Pandale and Val Verde points, and grooved rabbit sticks, various nets and woven items were found, in addition to Late Archaic dart points like the Shumla point, suggesting it was reused as a living space over a long period of time. Besides offering excellent shelter from the elements, archeologists have noted the presence of two natural springs below the shelter. Black manganese oxide and red iron oxide pigment rocks were recovered from this site, though there are no pictographs present on the cave walls (Maslowski). With these considerations, one can infer that multiple people groups might have been influenced, if not responsible for, the symbols and iconography in PRS pictographs in ancient times. While connections have been made to Huichol mythology, these sites may also be significant to the cultural development of Coahuiltecan groups, and sacred to their descendants.

Photo by the author, taken in January 2021 from deep within Moorehead cave, the openings of which face north. From the entrances, one can view a wide bend of the Lower Pecos River, directly below the cave.

The Huichol people, with a central population of about 10,000, live today in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico . There, they have fought brutal Spanish conquest on two different occasions in the 1500’s, and to this day they are known for maintaining their pre-Columbian spiritual practices. One of their most famous practices is the “Dance of the Deer,” or the pilgrimage to hunt peyote. The Huichol people have an oral history which is hard to trace, but their language is in the Uto-Aztecan family, which connects them to southern peoples like the Maya and the Aztec, as well as people groups as far north as the Hopi. This is why it is not hard to imagine that ancestors of the Huichol might have lived in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands in antiquity (Boyd and Cox; Myerhoff; Guiterrez).

I will argue in support of a connection that Boyd makes between a visual and cultural motif in PRS pictographs is the peyote-deer hunt, in which deer and peyote are two sides of the same coin to the modern day Huichol (Boyd and Cox; Neurath; Secunda). Peyote, only grows in this small area of Texas and in neighboring regions in México, and today only a small amount of peyote is distributed to the Native American Church in the U.S.. To the Huichol, the cactus is said to grow from the trail of the deer (Boyd and Cox; Secunda). Huichol peyotism is well-studied and their annual peyote-hunting ceremony traces back to their creation myth, which is acted out or re-experienced each year: the First Peyote Hunt. This ritual or pilgrimage involves the hunting of peyote (They are actually shot with an arrow, just like a deer) which is seen as a reiteration of the original creation-related myth of Kauyumari, the antlered shaman or deer deity. In this story, peyote was made from the sacrificed or transformed body of this deity or divine ancestor, who hunted a deer which was simultaneously himself. Kauyumari is responsible for opening up the portal to the otherworld in this act, and accordingly: Deer and peyote are associated with him and represent a bridge between the gods or spirits and the Huichol shaman. Shamans are both healers and spiritual leaders to the Huichol. Each year, five Huichol pilgrims and a shaman, carrying antlers, set out to hunt peyote. Upon finding the cacti, they shoot it, a solemn event, and guide the colorful kupuri, the soul of the deer and the peyote, back into the cacti, and the shaman selects five perfect cacti to bring back on the tines of the antlers (Neurath et al. et al.; Secunda; Guiterrez; Boyd and Cox).

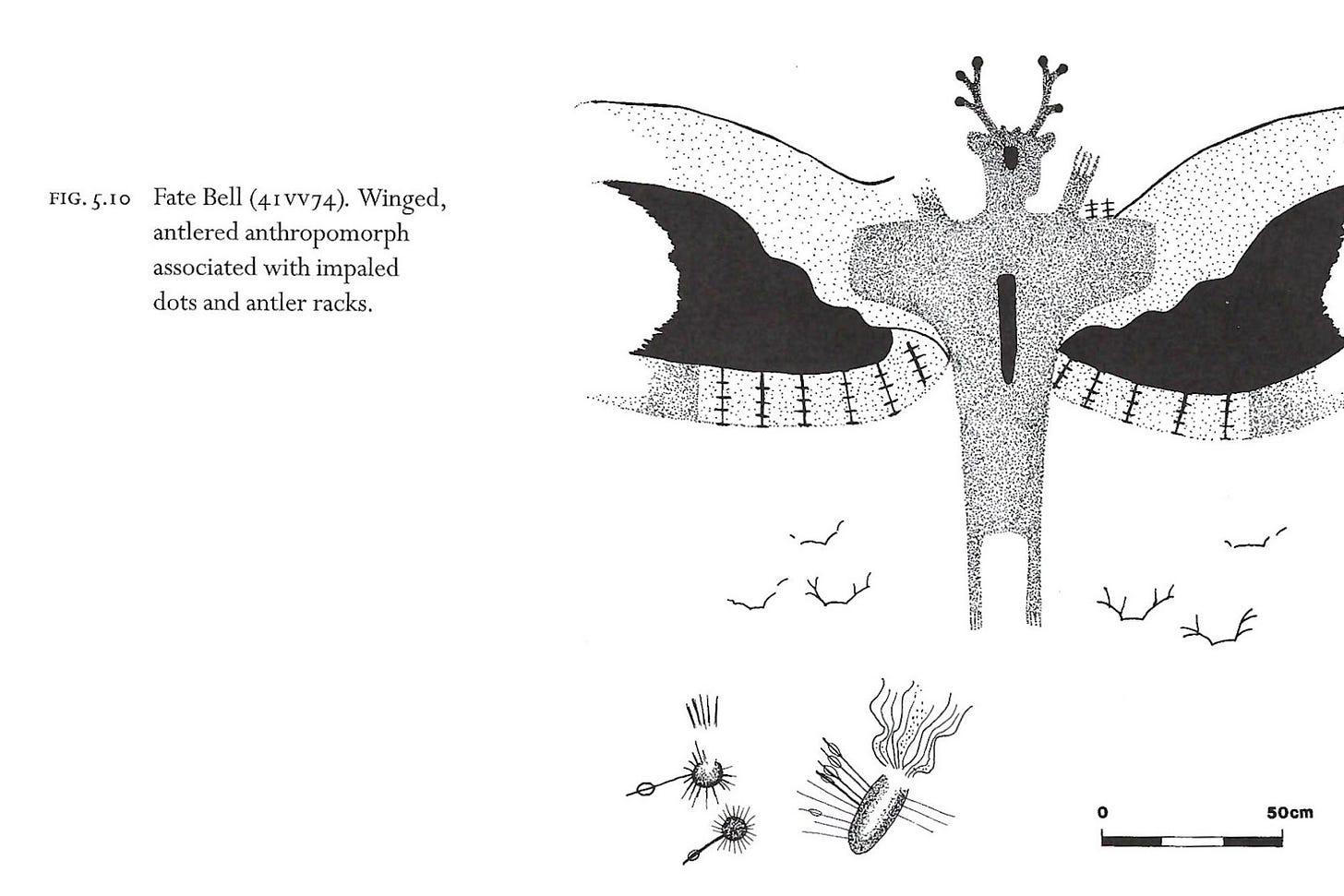

Details of this ritual are important for the relevant visuals that might be present in the rock art of the Lower Pecos-- slain deer, round dots with darts coming from them (which Boyd interprets as peyote buttons or cacti), antlered anthropomorphs, antlers with black dots on the tines, and the number five are recurring visual themes in this ancient rock art When these symbols are found on the same rock wall, the connection to this myth seems very possible. I found myself making many guesses at additional connections to these myths when I viewed the antlered figure at Fate Bell Shelter (Site 41VV74)

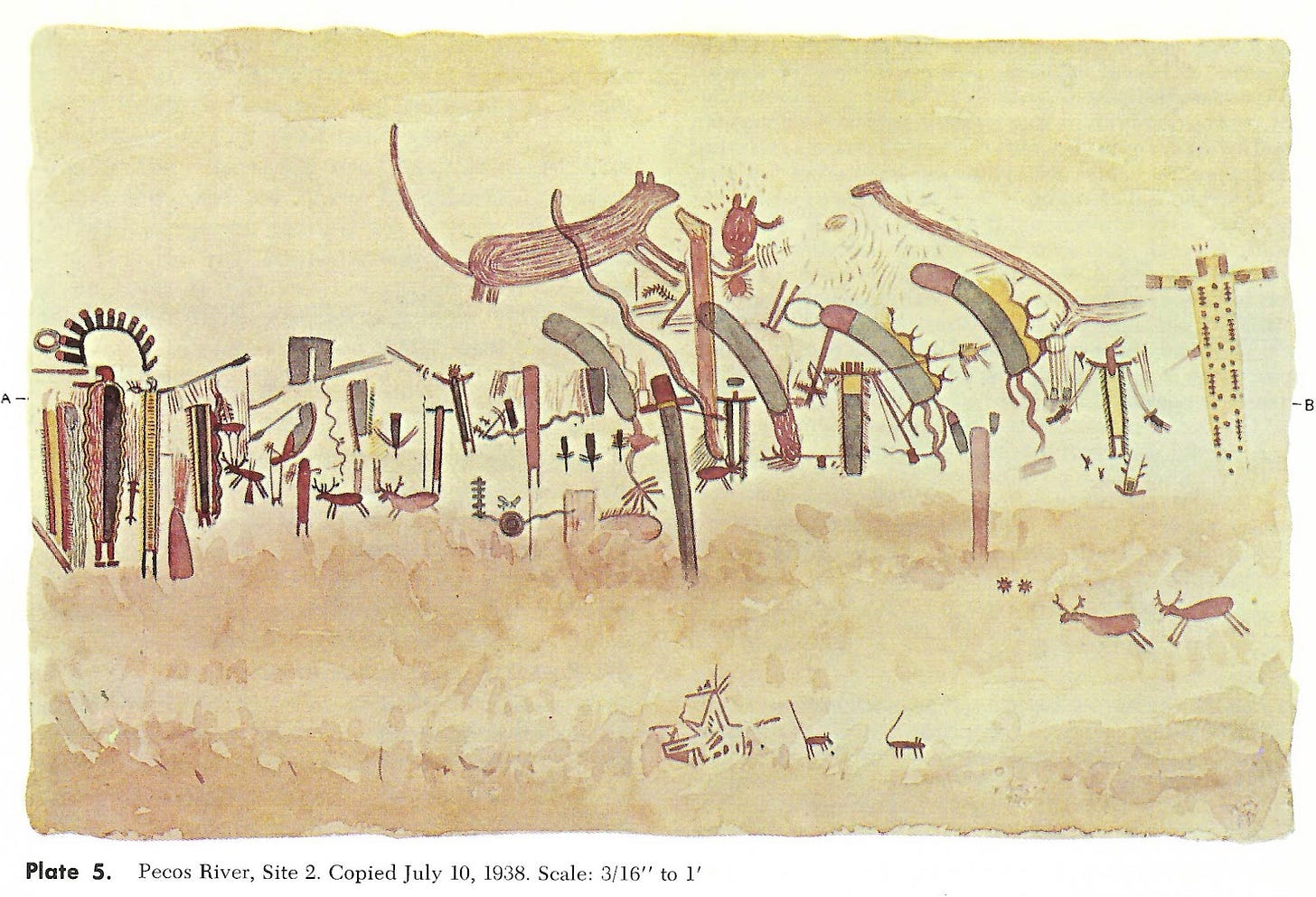

Top (Left): Fate Bell (41VV74) copied by Kirkland in July of 1936 in watercolor (Kirkland and Newcomb)

Bottom (Left): Photo of Fate Bell panel by the author showing the present color, texture, and spacing of the rock art in January 2021.

Right: Drawing by Boyd of a portion of the Fate Bell panel, showing the focus of the analysis for themes of peyotism and deer hunting/worship. Impaled dots, antler racks lie below a winged, antlered anthropomorph (Boyd and Cox).

However, as Boyd points out, neither peyotism nor these visual motifs are limited to the Huichol. Furthermore, she is not attempting to make a one-to-one comparison of the ancient people in the area to the Huichol. The people who left these pictographs could have completely different descendants for all we know. Even so, she hypothesizes that the people who made these pictographs found a connection between deer and peyote, and this was important in their ritual life in the Middle Archaic period (Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos). These ideas, if not transferred directly via Huichol ancestors, could have existed and influenced the ancestors of the Huichol.

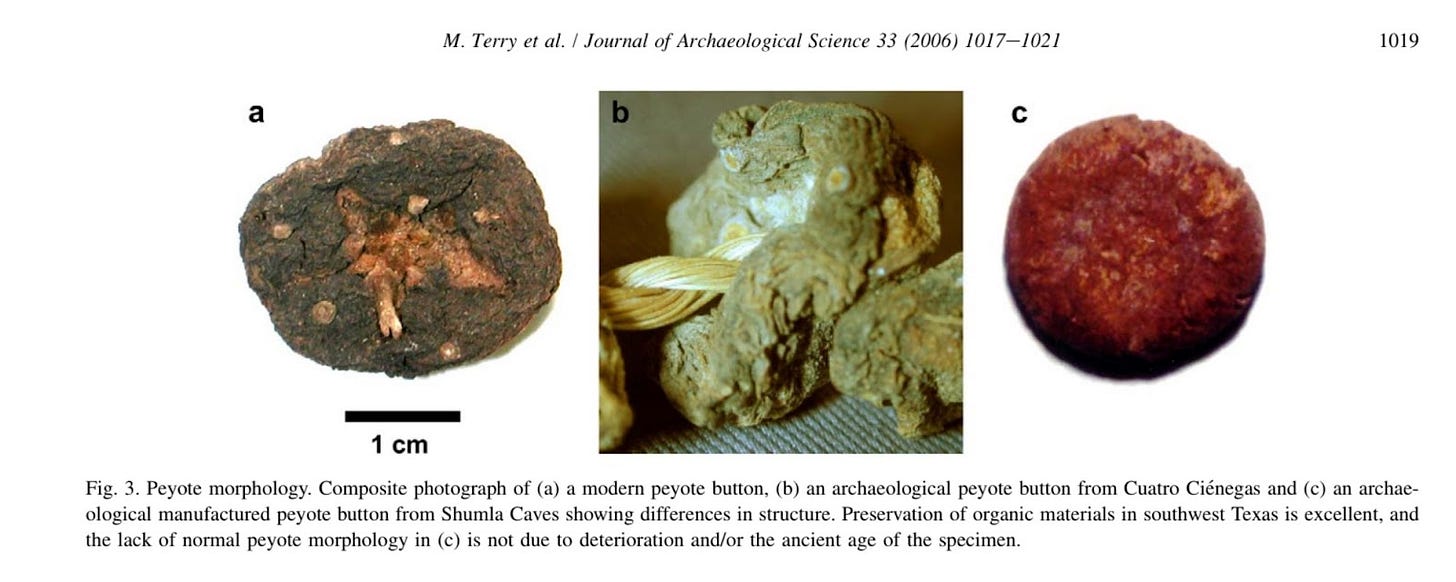

A recent carbon dating study by Terry et al. reported the dates of peyote specimens found in caves in the area supports Boyd’s hypothesis. Three mescaline-containing (2% mescaline) peyote specimens or “manufactured buttons'' excavated at Shumla Caves in Val Verde County, Texas, as well as a natural peyote specimen excavated from shelter CM-79, near Cuatro Cie ́negas, Coahuila (corrected for 𝜎13C). These peyote buttons are made of mixed C3 and C4 plants, indicating that the fibrous tissue of other plants besides the peyote cactus, Lophophora williamsii, were mixed in with these specimens by humans for unknown reasons, likely related to ritual or medicinal practice (Terry et al.).

These manufactured peyote buttons, paired with artwork and evidence of human activity in the areas in the same time periods, provides supporting evidence that the same people who lived, hunted, and left paintings (Depicting atlatls, darts, slain deer) in this area might have also become interested in the mescaline-containing peyote cactus, presumably for its psychoactive effects (and/or its medicinal use as an antibiotic). Considering the strong hallucinogenic effects of mescaline, this cactus would be a provocative source of creative inspiration for spiritual leaders, or shamans. Today, there are many peoples in the American Southwest and in Mesoamerica that consider the peyote cactus to be sacred. These Shumla Caves peyote specimens predate the neighboring pictographs in PRS, with the only painting samples dated to ~2,700 B.C.E.-- 400 C.E. in the Middle Archaic Period (Rowe; Boyd, White Shaman Mural book). However, dates of ~4,000 B.C.E. for the Shumla Caves buttons position them right at the beginning of the Middle Archaic Period, associating them with the same era as the pictographs in question (Terry et al.). The nearby site in México (Cuatro Cie ́negas, Coahuila) dates to several hundred years after the supposed end of the time span for PRS art, landing this specimen in the Late Prehistoric period (Terry et al.; Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos).

Ancient Peyote Specimens. Left (a): Modern peyote button for comparison. Middle (b): Cuatro Cienegas peyote button from archeological dig. Right (c): Manufactured peyote button recovered from Shumla Caves, dating to ~4,000 B.C.E., the beginning of the Middle Archaic period. (Adapted from Terry et al., “Lower Pecos and Coahuila Peyote: New Radiocarbon Dates.”)

With these radiocarbon dating studies in mind, it seems reasonable to connect peyotism to PRS rock art. In the desertous region in which these ancient people lived, there are seasonal and biological reasons to associate the life forms of deer and peyote as well. Rain after months of dry weather is known to attract deer to an area, where they seek new plant growth. Of course, hunter-gatherer societies would be very aware of the movement of deer, for the significance of their nutritional value. Rain also causes peyote to become more visible, as it swells with this rare moisture (Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos). Mescaline, the psychoactive alkaloid in peyote, causes powerful auditory, visual, and tactile hallucinations when taken in doses of 200-400 mg, with a long duration of action (Dasgupta). Mescaline has additional medicinal and therapeutic effects as an antidepressant in small doses. Specifically, mescaline is a 5-HT2A serotonergic receptor agonist, and recent neuroimaging studies have pointed to the beneficial effects of serotonergic agonist hallucinogens in altering emotional responses in social cognition (Rocha et al.). In 2016, another study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology reported improved mood regulation in the brains of recurrent depression patients after the administration of Ayahuasca, another 5-HT2A receptor agonist (Sanches et al.). These combined factors seem very likely to inspire story, myth, and artwork: When rain comes, the deer come, and peyote becomes visible. This brings new food, new spiritual or psychologically compelling experiences, and even medicine. As a spiritual leader as well as the community healer, the shaman would pay special attention to peyote and related natural cycles. The theme of shamanistic rituals being conveyed or translated through PRS pictographs would reasonably extend to this functional part of shamanistic life and leadership (Neurath et al.; Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos; Secunda).

Interpretation of White Shaman Mural (41VV124)

Photo by the author. The White Shaman Mural. (41VV124)

After reviewing the connections that Boyd made in her 2016 book to ethnographic literature, and viewing the White Shaman painting myself, I think that many shapes in this panel could relate to the theme of peyote/deer that appears throughout PRS rock art. The presence of slain deer next to an antlered anthropomorph, the five dark anthropomorphs spread evenly throughout and connected by a sinusoidal wave, the large multicolored catfish/serpent zoomorph, and the arch or hill-like shape on which the antlered anthropomorph stands provide the most basis for connection to the myths related to the First Hunt, which could be echoes of the old beliefs of people who lived in the region. These shapes also tie the composition together, leading the eye around the entirety of the wall. In the account of the Huichol First Hunt provided by Johannes Neurath, there are several characters that seem analogous to these shapes, as well as two simultaneous stories: The first deer hunt/peyote pilgrimage and the first sunrise. Five brothers or pilgrims, described as “seekers of dawn” and originally in animal bodies, follow the first being to emerge from the primordial ocean: The deer spirit. This character is described as a man with a deer head in some versions but also simply as a deer. They follow the deer to the East where they kill the deer, but the deer spirit is also seen as giving himself up or hunting himself out of pity for the hunters. At the same time, his heart turned into peyote, which the hunters ate the “meat” of (Boyd and Cox; Neurath et al.). On the “Hill of the Dawn,” a young hunter also threw himself onto a fire and emerged as the sun, which is also connected to light-- kupuri-- that is said to emerge from the first peyote cactus, or the deer’s heart, which the pilgrims ate (Neurath et al.; Secunda). The five black anthropomorphs, evenly spaced and seemingly connected with the curving white line, have been described by Boyd as primordial versions of the five brothers or original pilgrims. Today, Huichol pilgrims (In groups of five) still travel to Wirikuta lead by shamans, and in their cultural reality they do not merely reenact this story but physically become their supernatural ancestors/deities, by abstaining from sleep, sex, salt, and more as a way to become spirit-like. (Myerhoff)

Photo and digital rendering by Caroline E. Boyd of the White Shaman Mural (41VV124). Green: Five black anthropomorphs.

Blue: Slain deer. Orange: Catfish-resembling zoomorph.

Pink: Headless anthropomorph in white, dark gray, and red paint.

White: Serpentine line that changes from black to white as it passes through small antlered anthropomorph. Arrows added by the author (Photo from Rivard).

The white, serpentine line which covers much of the panel and superimposes all the figures serves the obvious visual role of connecting some of these main elements. But Boyd guessed at its role as a variably applicable symbol. Huichol pilgrims carry a cord which binds them together, uniting them as one through a metaphorical umbilical cord in ceremony (Boyd and Cox), but this white line might have represented additional or entirely separate meanings in antiquity. In Huichol mythology, the Kawi (meaning History, represented as a caterpillar) marked the path to the Hill of Dawn. The white line appears to transition to a black line on the left hand side of the panel (Or the black line transitions to white, from left to right), directly as it passes over both the top of the polychromatic arch and the body of the antlered anthropomorph. Boyd writes, “According to myth, Kawi’s path stops at the top of Dawn Mountain'' (Boyd refers to the Hill of Dawn as Dawn Mountain). Interestingly, two serpents represent the dry season and the rain season in the Huichol cosmology, and the dry season serpent is said to be white, while the rain season serpent is black. When combined with the motif of peyote and deer being associated with rain, this is certainly a compelling connection to make (Guitierrez; Boyd and Cox).

Boyd hypothesizes that this figure, along with the eerie, headless figure that so many call the “White Shaman,” might be an ancient version of what the Huichol today call Takutsi Nakawe, the Great-Grandmother of Growth, the root of all female essence and the ruler of the cosmos during the rain season (Schaefer 2002:50). She is understood in Huichol tradition as a goddess of both the earth and the moon, and is depicted as a catfish or a snake. She might have also been adapted in oral histories to become the eastern rain serpent goddess, Nia’ariwame (Preuss 1996:124). There are several mythological components that support this hypothesis, and the first relates to color. In Mesoamerica (In fact, in much of the Américas, and even Eastern Siberia), the four cardinal directions are assigned colors. The earliest artists’ color palette, which is made from accessible earth/mineral pigments, is as follows: White is north, red is east, yellow is south, and black is west (Boyd and Cox). The shared embodiment of Grandmother Growth with the eastern rain goddess means that the body of this goddess would be expected to be predominantly red-- and this figure is indeed painted in red. Additionally, a facet of the First Hunt or the peyote pilgrimage is that the five pilgrims become the goddess in the shape of a cloud to return home with the rains from the east (Neurath et al.; Boyd and Cox). The scale and three-dimensional effect of the pictograph is worth mentioning here. When I viewed this panel of pictographs, I was struck by how the top of the panel was so curved that the higher elements in the painting almost arches over the viewer. As I squatted underneath, the catfish-like zoomorph loomed above me-- not unlike rain clouds.

Photo by Veronique Tessier at site 41VV124, January 2021.

White paint, the last layer, was also used on the enigmatic “White Shaman,” according to Boyd. After carefully analyzing the order of which paints were laid down, she discovered that the white, headless anthropomorph is “interwoven,” layers of color both underneath and on top of, the catfish-like zoomorph and the black anthropomorph from which the white figure seems to emerge. According to the Huichol myth, the moon goddess made light for the pilgrims of the First Hunt during the night, and this character is closely tied to the Grandmother Growth as a female spirit or diety. She is also associated with the color white as a deity associated with the moon.

This brings us back to the theme of peyotism. Red dots impaled with red darts, possibly representing peyote, are painted underneath the white layer of the catfish zoomorph’s body, providing another connection to the motif of the importance of peyote/deer hunting to these ancient people.

Photo by the author. Catfish-like zoomorph, “White Shaman” anthropomorph, and curved white line demand the composition of PRS pictographs at site 41VV124

These connections are solid ground upon which we can assume the sacred nature of this site to indigenous peoples, and the importance of the art and surrounding archeological sites to their heritage and history. Peyote is a protected plant for its continued use in many native american and mesoamerican cultures. This leads to the very important message from these sites: Though we might not fully understand them in a Western academic setting, they must be protected for their cultural significance. The US Government signed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) in 2010, which states: “Indigenous peoples have the right to manifest, practice, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; ….” The Indigenous Cultures Institute is dedicated to this cause along with researchers like Boyd. They publicly state on their website that Coahuiltecan members and elders believe that the White Shaman panel contains elements of the Coahuiltecan people’s creation story after talking with archeologists like Boyd, and they believe that it documents the pilgrimage of their ancestors to gather sacred peyote in antiquity. These leaders have discussed this with Boyd, and the volunteer tour guides relay this to visitors of the panel, appropriately upholding the idea to visitors that this site is sacred (Sacred Sites – Indigenous Cultures Institute). Coahuiltecan elder Dr. Mario Garza said, while in front of the pictographs, “When I come here, I feel... that it (The White Shaman panel) is alive, that it is still telling us a lot of things. We have been able to study and interpret some parts of it but every time I look at it I see new things,” (NBC).

Discussion of Preservation Challenges:

PRS rock art is vulnerable to a number of sources of damage, and this is a major roadblock in the path of successful preservation of these culturally important and historic art sites. As most artwork is located in natural limestone overhangs, there is some protection on certain sites from direct rain, but a legion of other problems are present in all cases. In my visit via kayak to some of the less protected sites along the Pecos in January of 2021, I encountered some repeated issues that were more pronounced than the issues easily visible in the guided tours.

After the Rio Grande river was dammed up to make the Amistad Reservoir in 1969, flooding the lower canyons of the Pecos and Devil Rivers and covering up countless archeological sites, the water level has risen and humidified the region to some degree (Dering, “Lower Pecos Canyonlands”). Lichen grows along the cave and rock overhang surfaces, growing on the same flat limestone areas that were painted in ancient times. Mud Dauber wasps build their nests in these safe, out of reach areas… Directly on the rock art, in some cases. Time and exposure to the elements has faded pictographs in the area, but they are remarkably resistant to change considering how old they are. Spalding of weak limestone has removed pieces of these ancient panels as well. Humans, however, have caused a great deal of issues through vandalism and manipulation of these sites. Goats and sheep from nearby farmers have rubbed off lower portions of many of these paintings, and vandals have etched their initials or spray-painted tags onto the same rock walls that host ancient and sacred paintings, sometimes directly on the pictographs. I documented an example of initials scratched into what are likely Red Monochrome style pictographs at Coyote Shelter, a small site along the Lower Pecos that I saw from my kayak.

Top: “Pecos River Site 1”(Coyote Shelter) As copied by Kirkland in July of 1938

Bottom: Photo by the author of the same pictographs, with vandalism pointed out with an added blue arrow. The initials “KP” are scratched into the top coyote.

Site 41VV90 contains large, polychromatic elements in PRS, and spans a wide, sweeping limestone overhang surrounded by vegetation on a cliffside overlooking the Pecos river. The site is seriously faded and damaged, with many of the shapes that Kirkland copied on July 10, 1938 barely visible now. Kirkland recorded that the rock was flaking badly and hit by blowing rains from the east. However, the most drastic damage was from humans: “...heavy collection of dust was caused by an oil which had been painted over the best designs, evidently by someone who wanted to intensify their color for photographing,” (Kirkland and Newcomb 20). By now, after 83 or more years of dust accumulation, the artwork is very hard to make out. People who loot or dig in the deep cultural debris of the site while looking for artifacts kick up dust, which accelerates this dust accumulation. In the photo I took below, I used the software LabStretch to attempt to make the shapes more visible, but these are still obscured by gray dust accumulated on them.

Top: The first documentation of this site, the copy by Kirkland in 1938. The site lies on the west bank of the Pecos river, high on a cliffside bluff. Pictured is only one section of the very wide panel of PRS rock art (Kirkland and Newcomb 20).

Bottom: Photo of the site taken and edited by the author in January of 2021. Gray areas show increased dust accumulation covering the artwork. Edited with LabStretch.

Conclusions:

The loss of more PRS pictographs to time, damage, and weather is inevitable, yet the sad reality of damage from humans poses additional threats to these culturally significant and historic sites. Though there are serious challenges in preservation of the art itself, researchers are working hard to document it for continued study and appreciation. The leading team in conservation, documentation, and study of this artwork is the Shumla Archeological Research and Education Center. Led by Boyd, and collaborating with international researchers across many disciplines, this team has been accomplishing the meticulous documentation and study of many pictographs in the area, using techniques like 3D-mapping to preserve the art for future study. Thanks to Boyd’s research, the pictographs are now considered as written records of history, natural rhythms and cultural truths, conveying complex messages that might be able to be deciphered. Referring to each of these sites as “books,” and with high hopes of continued funding from donors, Shumla Center has embarked on what they are calling the Alexandria Project, an estimated $3 million endeavor to comprehensively document the entirety of the pictographic library of the Lower Pecos. This project will hopefully allow this library of ancient ideas and symbols to be studied for future generations (“Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center”).

In addition to their cultural significance and informative nature as “books,” these rock art sites deserve study and protection for their incredibly beautiful aesthetic qualities. The oxford dictionary defines art as “The expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.” These rock art sites, the creation of which might have been part of ritual or ceremonial practice, have remained relatively intact and colorful over thousands of years. This, in combination with the undeniable skill of their application, and the movement and striking visual elements in the paintings, are feats of artistic ingenuity worth celebrating in their own right.

What was it, some five thousand or more years ago, that inspired the people who lived there so much that they ground pigments, mixed nutritionally valuable fats into their paint, and possibly built scaffolding to paint these large pictographs (Boyd, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos; “Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center”)? Whether they were completed for the recording of myth, practice of ritual, or other purposes remains somewhat mysterious despite intensive research. Interpretations of themes evident in the artwork, paired with analogous artifacts in the archeological record, can lead to the inference that these paintings were related to ritual and shamanistic practice. In particular, there seems sufficient evidence to assume that peyote was celebrated in these paintings, and that it was important to the sacred and ritual life of people that visited these caves in the Middle Archaic period. This helps define these sites as sacred.

Who are the descendents of those who left the PRS pictographs? The Coahuiltecans recognize ancestral figures according to Mario Garza, PhD, a tribal elder. Dr. Mario Garzia and other leaders are fighting for the reburial of Texas Indian ancestors, as the remains of some 2,400 bodies are currently held by UT Austin (“Reburial – Indigenous Cultures Institute”). There is information in the paintings themselves that needs to be preserved and recorded which might lend additional understanding of the life of ancient peoples, when paired with archeological and biochemical research. Whether bodies or artwork, there is a need for respect & reverence, both for respect of humanity and cultural significance.

These are my reflections after just a few awe-inspiring moments of viewing human-made symbols from so long ago, rendered beautifully on natural and sturdy geological features in impressive scale, with fine detail, dynamic linework, and gorgeous use of mineral colors. As every great book or painting strives to do, PRS artwork tells the story of the human condition.

Sources:

Boyd, Carolyn E., et al. “A Reassessment of Red Linear Pictographs in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of Texas.” American Antiquity, vol. 78, no. 3, July 2013, pp. 456–82, doi:10.7183/0002-7316.78.3.456.

Boyd, Carolyn E. Rock Art of the Lower Pecos. Texas A & M University, 2003.

Boyd, Carolyn E. “Shamanic Journeys into the Otherworld of the Archaic Chichimec.” Latin American Antiquity, vol. 7, no. 2, June 1996, pp. 152–64, doi:10.2307/971615.

Boyd, Carolyn E., and Kim Cox. The White Shaman Mural : An Enduring Creation Narrative in the Rock Art of the Lower Pecos. University Of Texas Press, 2016.

Boyd, Carolyn E., and J. Philip Dering. “Medicinal and Hallucinogenic Plants Identified in the Sediments and Pictographs of the Lower Pecos, Texas Archaic.” Antiquity, vol. 70, no. 268, June 1996, pp. 256–75, doi:10.1017/s0003598x00083265.

Castañeda, Amanda M., et al. “Portable X-Ray Fluorescence of Lower Pecos Painted Pebbles: New Insights Regarding Pigment Choice and Chronology.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, vol. 25, June 2019, pp. 56–71, doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.03.013.

“Coahuiltecan Language and the Coahuiltecan Indian Tribe.” Www.native-Languages.org, www.native-languages.org/coahuiltecan.htm. Accessed 4 Feb. 2021.

Dasgupta, Amitava. “Chapter 33 - Abuse of Magic Mushroom, Peyote Cactus, LSD, Khat, and Volatiles.” ScienceDirect, edited by Amitava Dasgupta, Academic Press, 1 Jan. 2019, pp. 477–94, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128156070000332.

Dering, Philip J. “Lower Pecos Canyonlands.” Texasbeyondhistory.net, texasbeyondhistory.net/pecos/index.html. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Dering,“Lower Pecos-Archeology.” Texasbeyondhistory.net, texasbeyondhistory.net/pecos/archeology.html. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Dering, “Lower Pecos-Rock Art.” Texasbeyondhistory.net, texasbeyondhistory.net/pecos/art.html. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Kirkland, Forrest, and William W. Newcomb. The Rock Art of Texas Indians. Austin, University Of Texas Press, 1967.

Maslowski, Robert. The Archeology of Moorehead Cave, Val Verde County, Texas. 1978, pp. 1–332.

NBC. “Coahuiltecans, the First People of Texas - YouTube.” Www.youtube.com, 30 Apr. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=6fFAsctc7Qs.

“Reburial – Indigenous Cultures Institute.” Indigenous Cultures Institute, indigenouscultures.org/reburial/. Accessed 4 Feb. 2021.

Rivard, Robert. “Ancient Human Echoes in the Rock Art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.” San Antonio Report, 21 July 2018, sanantonioreport.org/ancient-human-echoes-in-the-rock-art-of-the-lower-pecos-canyonlands/.

Rocha, Juliana M., et al. “Serotonergic Hallucinogens and Recognition of Facial Emotion Expressions: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, vol. 9, Jan. 2019, p. 204512531984577, doi:10.1177/2045125319845774.

Rowe, Marvin W. “Radiocarbon Dating of Ancient Rock Paintings.” Analytical Chemistry, vol. 81, no. 5, Mar. 2009, pp. 1728–35, doi:10.1021/ac802555g.

Sacred Sites – Indigenous Cultures Institute. indigenouscultures.org/sacred-sites/. Accessed 4 Feb. 2021.

Sanches, Rafael Faria, et al. “Antidepressant Effects of a Single Dose of Ayahuasca in Patients with Recurrent Depression.” Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, vol. 36, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp. 77–81, doi:10.1097/jcp.0000000000000436.

Schmal, John P. “Indigenous Coahuila de Zaragoza: Land of the Coahuiltecans.” Indigenous Mexico, 6 Sept. 2019, indigenousmexico.org/coahuila/indigenous-coahuila-de-zaragoza/.

Secunda, Brant. “SHAMANISM | Huichol Tribe of Mexico’s Sierra Madre Mountains.” SHAMANISM, www.shamanism.com/huichol#tab-id-3. Accessed 4 Feb. 2021.

Shafer, Harry J., et al. Ancient Texans : Rock Art and Lifeways along the Lower Pecos. Published For The Witte Museum Of The San Antonio Museum Association By Gulf Pub. Co, 1992.

“Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center.” Shumla, shumla.org/. Accessed 3 Feb. 2021.

Terry, Martin, et al. “Lower Pecos and Coahuila Peyote: New Radiocarbon Dates.” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 33, no. 7, July 2006, pp. 1017–21, doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.11.008.